Although the origin of this phrase is a matter of debate, many claim it is an ancient curse of Chinese origin. For me, the first and lasting encounter with the phrase was its use in a 1966 speech by Robert F. Kennedy. RFK said “There is a Chinese curse which says ‘May he live in interesting times.’ Like it or not we live in interesting times. They are times of danger and uncertainty; but they are also more open to the creative energy of men than any other time in history.”

I relocated to Japan this year recognizing that I was departing my native land in the midst of a period of chaos and disorder as a result of Trump’s presidency. Since arriving in Tokyo, developments have only heightened my concern and focused my attention on the realization that there was no escape anywhere from living in a world made more dangerous and tumultuous by Trump.

It is evident that my adopted country of Japan also faces many challenges at home and abroad. I find it disturbing how much negative influence Trump’s behavior and policies have on Japan’s domestic and international strategies and plans. An obvious desire to please and appease Trump on a host of critical issues significantly hamper Japan’s opportunity to advance important policy initiatives.

In the domestic economic arena Japan remains mired in a period of economic stagnation that predates Trump’s election. While the Abe government’s policies have failed to reverse this condition, persistent structural issues represent an overwhelming challenge and serious threat to Japan’s future.

Foremost is the compounded impact of a declining but fast aging population, a low birthrate, and reduced size of the working age segment. This is further complicated by the continued marginalization of women in the workforce and a failure to address adoption of an immigration policy to effectively deal with the current and growing shortage of workers.

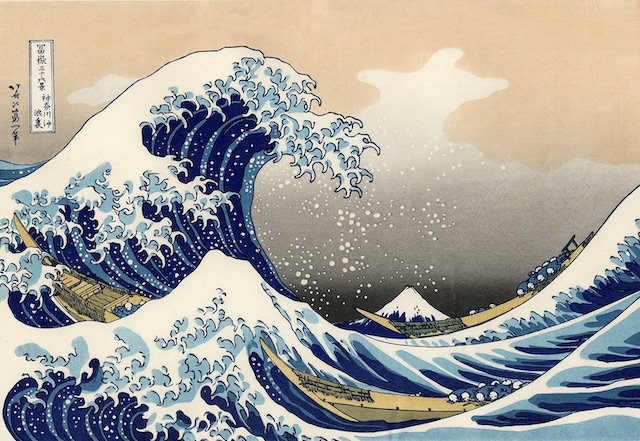

Japan’s vulnerability to devastating natural disasters like earthquakes, tsunamis and typhoons is also a great concern. The evident impact of climate change requires a more aggressive approach to environmental and sustainability issues.

The route to recovery is also dependent on Japan’s trade policies and relationships with the United States, China, the EU and Indo-Pacific region countries. Trump’s pulling the United States out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership free trade pact after his election signaled a serious problem. His trade warfare with China and a policy to pursue bilateral negotiations with other U.S. trading partners under the threat of punitive tariffs has greatly complicated Japan’s effort to reach multilateral free trade agreements.

For example, with the recent limited bilateral U.S.-Japan trade pact the Trump administration has managed to resolve its disadvantage in Japan’s agricultural market––a clear Abe political gift to golf-buddy Trump––that appears to offer little benefit to the Japan economy. In fact, Trump’s threatened imposition of further automotive tariffs undercuts its minimal positive economic impact and raises serious questions about the real value to Japan of Abe’s personal relationship with Trump.

Automotive trade accounts for 75 percent of the U.S. trade deficit with Japan. The fear is that with its “America First” protectionist agenda and Trump’s constant reference to the “very large” U.S. trade deficit with Japan, the Trump administration may now use its threat to impose numerical curbs on vehicle imports from Japan or heavy tariffs on Japanese auto and auto parts imports into the U.S. to place greater pressure on Abe in an effort to conclude trade and defense agreements under more favorable terms for U.S. interests.

In fact, Japan now finds itself in a much more insecure external environment that reflects, in part, the impact of Trump’s bewildering tenure.

While Japan faces strained relations with South Korea, North Korea’s provocative missile and nuclear ambitions, China’s increasingly growing military assertiveness in the region and Russia’s determined interest to the north, these perplexing regional issues are made more complex by Japan’s paradoxical uncertain relationship and dependence on the United States under a Trump presidency.

Trump’s contemptuous attitude toward allies, recently confirmed by his disdainful treatment of the Kurds, alone is sufficient reason for concern. His demand for a five-fold increase in Japan’s payment for future U.S. military support in the face of his dismissive view of North Korea’s missile threat, has legitimately made Japan increasingly uneasy about the long-standing defense commitment of the United States.

It is alarming but no longer unrealistic to consider that Trump could undermine an alliance system that has delivered peace and stability for so many decades.

With little I can now do at age 76 to influence events that will determine the policies and behavior of either the United States or Japan, I am nonetheless excited to be an observer “living in interesting times.” I only pray that the “creative energy of men” envisioned by RFK will be able to make the world a safer and better place to live.

The guide explained that the proper way in which to pray to this particular type of Jizo statue is to first p

The guide explained that the proper way in which to pray to this particular type of Jizo statue is to first p